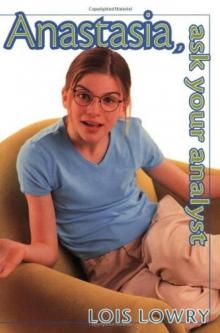

Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst, Page 1

Lois Lowry

ANASTASIA ASK YOUR ANALYST

Lois Lowry

* * *

Houghton Mifflin Company Boston

* * *

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Lowry, Lois.

Anastasia, ask your analyst.

Summary: Anastasia's seventh-grade science project

becomes almost more than she can handle, but brother

Sam, age three, and a bust of Freud, aid her nobly.

[1. Gerbils—Fiction. 2. Brothers and sisters—Fiction] I. Title.

PZ7.L9673Amc 1984 [Fic] 83-26687

ISBN 0-395-36011-0

Copyright © 1984 by Lois Lowry

All rights reserved. For information about permission

to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue

South, New York, New York 10003.

Printed in the United States of America

HAD 20 19 18 17 16 15

* * *

For the child in Nebraska

who wrote and suggested

that the Krupniks should have pets,

and Sam should have

a friend

1

"Mom!" shouted Anastasia as she clattered up the back steps and into the kitchen after school. "Guess what Meredith Halberg gave me! Just what I've been wanting! And it didn't cost anything!"

Mrs. Krupnik put a casserole into the oven, closed the oven door, and adjusted the temperature. She turned around. "Let me think," she said. "Chicken pox?"

Anastasia made a face. It was terrible, having a mother who always made jokes. "Ha ha, very funny," she said. "I said it was something I'd been wanting. Anyway, I had chicken pox years ago."

"Well," said her mother, "I can't think of anything else that doesn't cost anything."

Anastasia was so excited she was almost jumping up and down. "You'll never guess! Wait, I'll show you. They're on the back porch. They're probably getting cold. I'll bring them in."

"Hold it," her mother said. She looked suspicious. "What do you mean, they're getting cold? It's not something alive, is it?"

But Anastasia had already gone, banging the door behind her. In a minute she was back, holding a wooden box with a wire mesh cover over it. A rustling sound came from the inside of the box.

Her mother retreated instantly, behind the kitchen table. "No!" she said. "It is something alive! Anastasia, absolutely not! I've told you and told you that I can't stand—"

Anastasia wasn't listening. Her mother was so boring sometimes. She undid the latch and lifted the cover of the box.

"Gerbils!" she announced with delight.

Her mother backed away until she was against the refrigerator. She picked up a wooden spoon and held it like a weapon. "GET THOSE THINGS OUT OF MY KITCHEN IMMEDIATELY!" she bellowed.

"But, Mom, look how cute they are—"

"I SAID, OUT OF MY KITCHEN!"

Grouchily, Anastasia covered the box again. She took it to the back hall.

"Mom," she said when she returned, "you can open your eyes now. They're in the back hall."

Her mother sat down and took some deep breaths. She looked around warily. "Anastasia," she said, "you know I can't stand rodents."

"Mom, they're sweet, furry little—"

"Rodents." Her mother shuddered.

"Well, maybe. But, Mom—"

Her mother laid the wooden spoon on the table. She took another deep breath. "Rodents make me faint," she said. "I very nearly passed right out cold when you started taking the lid off that box."

Anastasia sighed. There wasn't another kid in the whole town who had a mother so idiotic. Coffee, she thought, coffee will help. She took the coffeepot from the stove and poured her mother a cup.

"Let's have a reasonable conversation about this subject," she suggested, handing her mother the cup of steaming coffee.

Her mother sipped, and shuddered one more time. "Tell me one reasonable reason for having disgusting rodents in this house," she said grimly.

"I can tell you lots more than one. The first is that I really need a pet."

"You have one. You've had Frank Goldfish since you were eight years old. I thought you loved Frank."

"I do love Frank, but he's boring. You can't teach him tricks. You can't cuddle him."

"You want to teach tricks to—you want to cuddle those—what are they called?"

"Romeo and Juliet. I named them on the way home."

"I don't mean names. I meant—what did you say they are?

"Gerbils."

"Okay, then. If you want to teach tricks to gerbils, I suggest you start by teaching them to walk on their cute, furry little hind legs. Right through the back door, down the steps, across the street, around the corner, and back to Meredith Halberg's house."

"Mom, that's stupid."

Her mother sighed. "I know it's stupid. But, Anastasia, honestly, I have this rodent phobia."

"I can see that. You look very pale. I'm really concerned about you, Mom. That's why it's important to get used to Romeo and Juliet and overcome this very serious phobia that you have."

Her mother groaned. At least she wasn't screaming no anymore. That was a good sign.

"Reason number two," said Anastasia. "They're going to be my Science Project. The Science Fair is in February, and I'm the only kid in the seventh grade who hasn't chosen a project yet."

"I told you to do the life cycle of the frog. I told you I'd help you make a huge poster describing the life cycle of the frog."

"For pete's sake, Mom, that's something you do in third grade. Everybody in the entire world has already done the life cycle of the frog, in third grade. This is junior high. This guy in my class—Norman Berkowitz? He's building a computer for his Science Project."

"Norman Berkowitz's father won the Nobel Prize in Physics last year," Mrs. Krupnik pointed out. She got up and poured herself another cup of coffee.

"Well," said Anastasia sulkily, "so what. Big deal. Dad was nominated for the American Book Award last year. The daughter of the person who was nominated for the American Book Award can't turn up at the Science Fair with a dumb life cycle of the frog poster, for pete's sake."

"What on earth could you do with a couple of smelly rodents?"

"They're not smelly," said Anastasia angrily. "I'm going to mate my gerbils, and then—"

"You're going to what?"

"Mate my gerbils. Then I'll study the pregnancy, and make notes, and observe their babies. I'll learn everything to know about—"

"OVER MY DEAD BODY ARE YOU GOING TO MATE RODENTS IN THIS HOUSE."

Whoops. She was losing ground, Anastasia knew. Time to present reason number three.

"Mom," she said calmly, "you're being unreasonable and irrational again. Here's reason number three. Think about Sam."

"I am thinking about Sam," said Mrs. Krupnik forcefully. "I do not want a three-year-old playing with nasty, filthy, little—"

"Mom, gerbils are clean. Be calm now. You know how you're always saying that sex education should begin in the home."

Her mother was starting to take deep breaths again, a bad sign. She sipped her coffee. "That's true," she said. "I do say that. What does that have to do with rodents?"

"Gerbils. Practice saying gerbils, Mom."

"Gerbils, then. What about sex education and gerbils? And what about Sam?"

"It's Sam's chance for sex education—right here in his very own home! He can see my gerbils having babies! Sam doesn't know anything about sex yet."

"Anastasia," her mother said and sighed. "Sam's not interested in sex. He's only three."

"But he's super-intelligent, Mom. You know how in

terested he is in everything. You know how he's starting to learn to read, and he knows all the letters, and all the numbers, and—"

"That has nothing to do with sex."

"I bet you anything that Sam is very interested in sex."

"Bet you he isn't."

Anastasia thought for a minute. If she did this right, she would win. But it would be tricky.

"Where is Sam?" she asked casually.

"In the living room, playing."

"Tell you what," Anastasia suggested. "Let's ask him. Let's ask him if he's interested in sex, and if he says yes, can I keep Romeo and Juliet?"

"No way," said her mother. "It wouldn't be fair, because the instant he sees them, he'll say he's interested."

"I won't let him see them. I won't even mention gerbils. It'll be a fair test."

Her mother gulped the last of her coffee while she thought it over. Finally she said, "Okay, but here are the rules. I'll call Sam in, and I'll ask him. And you are not to say a word about gerbils or gerbil babies. Not one word, understand?"

Anastasia nodded. "I won't. We'll only ask him if he's interested in sex."

"I'll ask him. You keep your mouth completely shut."

Anastasia clamped her mouth closed. She sucked her lips in between her teeth.

Her mother examined the clamped-mouth face. "Okay," she said.

She put her empty coffee cup in the sink, went to the kitchen door, and called, "Sam? Would you come in here for a minute? I want to ask you something."

They could hear Sam's little feet trotting down the hall. He appeared in the kitchen door, grinning, with his blue jeans sagging and his sneakers untied.

"Hi, Anastasia!" Sam said. "Today at nursery school I did blocks. All the blocks have letters. I can spell my name with blocks, and I can spell 'airplane,' and 'cookie,' and—"

Anastasia smiled at him and didn't say anything. She kept her mouth clamped closed.

"Sam, old buddy," said Mrs Krupnik casually, "I have a question I want to ask you."

"Okay," said Sam happily. "Can I have a cookie?"

Anastasia handed him a raisin cookie from the cookie jar. She kept her mouth tightly closed.

"Sam," said his mother, "are you interested in sex?"

Sam had stuffed half a cookie into his mouth. He chewed solemnly.

"Sam?" asked his mother.

"I'm thinking," he said, with his mouth full. "I'm giving it serious thought."

Finally, after he had swallowed, he asked, "How do you spell it?"

Anastasia grinned. Victory was in sight. She began to open her mouth to say "S." But her mother glared at her.

"Anastasia," Mrs. Krupnik said in warning, "keep your mouth absolutely shut, or our bet is off."

To Sam, Mrs. Krupnik said, "S-E-X."

Sam chewed the other half of his cookie slowly. He frowned. He was thinking. You could always tell when Sam was thinking because his forehead wrinkled up.

"I'll be back in a minute," he said suddenly, and trotted out of the kitchen.

Anastasia sat very still with her mouth tightly closed. Her lips were beginning to ache.

Then Sam reappeared. "Yes," he announced. "I am very interested in sex." And off he went, back to his game in the living room.

Mrs. Krupnik stared at Anastasia. Her eyes narrowed into a suspicious look. "All right," she said, finally. "A bet's a bet. You win."

Anastasia relaxed her mouth and wiggled her tongue a bit to make sure it still worked. She grinned. "Thanks, Mom," she said.

"You tricked me somehow. Tell me how."

Anastasia took a cookie and began to pick the raisins out, one by one. She popped them into her mouth. She didn't say anything.

"Why am I always outsmarted by a thirteen-year-old? Tell me how you did it!"

Finally Anastasia shrugged. "It wasn't a trick. It was just that I've been teaching Sam to play Scrabble. I knew when he left the kitchen that he was going off to check the Scrabble points in 'sex.' X is one of his favorite letters. Eight points for an X." She broke off a bit of the raisinless cookie and put it in her mouth.

Her mother watched her chew. After a moment she said, "Someday, Anastasia, I am going to offer you for adoption."

"Me and my gerbils, right?"

Science Project

Anastasia Krupnik

Mr. Sherman's Class

On October 13, I acquired two wonderful little gerbils, who are living in a cage in my bedroom. Their names are Romeo and Juliet, and they are very friendly. They seem to like each other a lot. Since they are living in the same cage as man and wife, I expect they will have gerbil babies. My gerbil book says that it takes twenty-five days to make gerbil babies. I think they are already mating, because they act very affectionate to each other, so I will count today as DAY ONE and then I will observe them for twenty-five days and I hope that on DAY 25 their babies will be born.

This will be my Science Project.

"What are you writing?" asked Sam. He was on his knees on Anastasia's bedroom floor, one arm in the gerbil cage as he stroked the heads of the furry creatures with his fingers.

"My Science Project for school," Anastasia explained. "I'm telling about Romeo and Juliet."

Sam looked up and frowned. "These are partly my gerbils, right?" he asked.

"Sure. It was because of you that I got to keep them. So I guess they're partly yours."

"Well, I want to name one Prince," said Sam.

Anastasia made a face. "Prince is a dog's name," she said.

Sam sighed. "Yeah," he said. "I really wanted a dog. I could play with a dog."

"You can play with the gerbils. Gerbils are friendly."

"These gerbils aren't. Look. They're biting each other." Sam pointed his finger into the cage.

Anastasia looked. Sam was right. The two gerbils were tussling with each other, their little teeth exposed.

"That's a domestic fight, I think," she told her brother. "Like when Mom and Dad have an argument. These gerbils are husband and wife, so of course they have little fights now and then."

Sam looked at the gerbils dubiously. "They're kind of ugly," he said. "And they're fat."

Anastasia closed her notebook and sighed. "Quit complaining, Sam. They're fat because they eat a lot. And they're not ugly."

"That one," said Sam, pointing, "is very, very ugly. Can I name that one Nicky?"

"No," said Anastasia impatiently. "Why on earth would you name a gerbil Nicky?"

"Because it looks like an ugly kid at my nursery school. Nicky. Nicky is the ugliest person I know. And fat, too. Nicky is very fat and very ugly, just like these gerbils, and Nicky also bites."

Anastasia glanced out of her bedroom window, down into the yard where her father was raking leaves. "Sam," she said, "why don't you go down to the yard? Maybe Dad will let you jump into the leaf piles."

"Are you going to come and jump in leaf piles with me?"

"No," Anastasia sighed. "I have to stay here and observe the gerbils. For my Science Project. Close the door when you leave. I promised Mom that she would never hear one single gerbil noise from my room."

Sam latched the lid of the cage and headed for the door. "I wish you were doing a dog for your Science Project," he said wistfully, "so I could name it Prince."

2

Anastasia came in from school, dropped her books on the kitchen table, rummaged through the refrigerator until she found something that looked appealing—a piece of cold chicken, which she dipped in some mustard—and then headed up the back stairs to her room.

At the closed door of her bedroom she stopped, startled. Her way was blocked by the vacuum cleaner, which was sitting in the middle of the hall floor. Attached to it with a piece of Scotch tape was a note.

"Anastasia," the note said. "You realize that I can't possibly clean your room anymore, since you have those things in there, and I suffer from this phobia. Be sure to do in the corners, and under the bed. Put the vacuum cleaner away in the hall closet when you're done. Lo

ve, Mom."

"LOVE, MOM"?Did Hitler sign notes "Love, Adolf"?

Anastasia glowered, and went back downstairs in search of her mother. "Love, Mom" indeed!

Mrs. Krupnik, wearing jeans and a paint-spattered man's shirt, was sitting on the floor of the room that she used as her artist's studio. Beside her was Sam, squatting on his short three-year-old legs. His face and clothes and hands were daubed with different colors. He grinned up at Anastasia and then went back to stirring a coffee can filled with bright orange paint.

There were oatmeal boxes all over the floor of the big room, on top of newspapers. Two of the boxes had been painted bright blue; the others were waiting. The Quaker Oats man was smiling his patronizing smile at Anastasia. That was all she needed, to be leered at by Mr. Quaker Oats when she was already furious.

"I hate that guy's looks," Anastasia said, frowning. "He looks so wholesome. I wish someone would make him eat sugary cereal filled with chemical additives."

"Goodness. Why are you so grouchy?" asked Katherine Krupnik.

"Three guesses," said Anastasia, glaring at her mother.

Mrs. Krupnik picked up one of the empty boxes, studied the Quaker Oats man for a minute, and then painted an orange mustache on his face with a flourish. "I think he's cute," she said. "He has a benevolent look. I like Quakers in general. I just wish I liked oatmeal better. It's taken two years to save up these boxes."

"I SAID, THREE GUESSES," Anastasia repeated loudly.

Her mother smiled at her pleasantly. "I don't want to discuss it," she said. "You told me you'd keep them completely out of my sight. Okay. That means you clean your own room, kiddo."

"We're making a train!" announced Sam gleefully. "The blue ones are going to be the boxcars, and now we're going to do orange, and they'll be the—what are they going to be, Mom?"

"Cattle cars," said Mrs. Krupnik. "And we'll have a green coal car, and a black engine with silver trimming, and of course the caboose will be red—"

She interrupted herself. "Here, Sam," she said, handing him the box she was holding, "take this one with the mustache and paint the whole box orange."