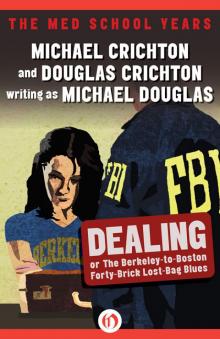

Dealing or The Berkeley-to-Boston Forty-Brick Lost-Bag Blues, Page 1

Michael Crichton

Dealing

Or The Berkeley-to-Boston Forty-Brick Lost-Bag Blues

Michael Crichton and Douglas Crichton, writing as Michael Douglas

ALL NAMES, CHARACTERS, AND EVENTS IN THIS BOOK ARE FICTIONAL, AND ANY RESEMBLANCE TO REAL PERSONS IS EITHER COINCIDENTAL OR THE RESULT OF STONED PARANOIA.

To the lawmakers of our great land:

Play This Book LOUD!

Most of what my neighbors call good,

I am profoundly convinced is

evil, and if I repent anything, it is

my good conduct that I repent.

THOREAU

When somebody like Timothy Leary

comes out and justifies [using

drugs], we’ve got to jump on him

with hobnailed boots.

LINKLETTER

I knew I was going off (hard)

drugs when I didn’t like to watch TV.

BILLIE HOLLIDAY

Contents

1: Viper’s Tangle

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

2: Fattening Frogs for King Snakes

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

3: A Taste of Soup

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

A Biography of Michael Crichton

1

Viper’s Tangle

The sky is high, and so am I—

if you’se a viper.

FATS WALLER

1

AS A STANDBY YOU GET the seat right behind the jets. Sit down, tuck the special suitcase under the seat in front of you, buckle up, and look out the window at the Boston rain. Then look over and smile at the two Marines sitting next to you, and wait for the goddamned thing to take off.

Once in the air, you get your choice of chicken, sword-fish, or roast beef; Life, Vogue, or Sports Afield. Life features an article on the growing menace to our children, the Marijuana Habit. A follow-up on how one Illinois town rallied to the challenge and pulled itself out of the dope gutter. A quote from a kid at the University of Illinois who says reality is the best trip of all.

When you can’t stand any more, you up and amble back to the can and flip on the OCCUPIED sign. Once safely locked in, you fumble around with the air whooshing up out of the john; you try not to spill your whole stash on the floor as you roll a neat little joint in your clammy dope-fiend hands. And then you blow it.

After that, things slow down a bit and you amble back and stumble across the two Marines and get your earphones on just in time to catch the flick. Last time it wasn’t too bad, some Nazis torturing a prostitute, but no such luck on these daytime ventures—it’s Andy Griffith as an iconoclastic but truly lovable parish priest. For the next two hours you are part of Andy’s G-for-General-Audiences struggle to refurnish the church, and it’s all pretty wonderful. But toward the end of the movie, high-altitude dehydration sets in, and you find yourself feeling pretty miserable. So you amble back toward the can again, with numerous eyes flicking up at you suspiciously as you walk down the aisle—since everybody smelled dope the last time—but you fool them all and get a cup of water.

While you’re in the galley you pocket a few of those absurd little booze bottles that they hustle for a buck apiece before the meal, have a few more cups of water, turning occasionally to face the cabin, and smile innocently at anyone who is looking. Then return to your seat, with some ice in the cup, to get thoroughly and quietly juiced.

This doesn’t help the dehydration any but it makes the time go a lot faster. Toward the end of the trip you even join the Marines in molesting the stewardesses. The stewardesses are very good-natured about them, because they’re in uniform, poor fellows, and so young, too. The stewardesses are less good-natured about you.

Finally the captain comes on to announce that San Francisco airport is still there, and that we may be landing soon. The seat belt sign comes on, the Muzak returns, and everyone frantically puffs away, trying to get that last little hit of nicotine before the NO SMOKING sign flashes on. Behind you in the next seat the middle-aged lady searches her purse for the tranquilizer she always drops before the landing.

And then the plane comes down. It’s 3:55 P.M. Pacific Standard Time, seventy-two degrees, the sun is shining on both sides of the street, and it’s all before you.

2

I WAS EXPECTING TO BE met at the airport, but nobody showed. I couldn’t believe John hadn’t called my friends to let them know I was coming, so I shuffled up and down the arrivals platform waiting for a familiar face. Everyone was waiting. There were servicemen waiting for the bus, businessmen waiting for the fat wife and the dog, porters waiting for tips; all of us waiting to see what would happen and waiting then to see what would come next.

After an hour I knew John hadn’t called. It pissed me off that he could be so casual. He could afford to be, that was the heart of the matter. John had enough bread to buy himself out of anything that he got into—and into anything he felt out of. He simply assumed things were the same for other people—and if they didn’t measure up to the assumption, then what the hell were they doing hanging around with him? But I was still angry, because I couldn’t take a bus across the Bay, not with twenty-five hundred in twenties bulging in my coat pocket. The only alternative was a rented car, and he knew that I didn’t have the bread to waste on a rented car. But then, he did …

So I went over to the Hertz counter, where a sleazy blonde in a zebra suit was smiling into space. She could be easily replaced by a machine that smiled, I thought as I stepped into view. But then a machine would have known that my license was a phony. And anyway it was all part of the game: I gave her the license and she smiled. I pretended the smile was real, and she pretended the license was real. A reasonable bargain, all things considered.

The car was a green ’69 Mustang. First thing I did when I got in was to check the ashtray. A ridiculous gesture, but the kind of thing I always find myself doing, just to make sure that the ads are really up front. Yeah. Well, the ashtray was clean but the ignition was burned out and the car wouldn’t start, so I exchanged it for an identical green Mustang and rolled out to Berkeley.

Back on the Bay Shore Freeway. It felt good to be ripping along at sixty-five miles an hour, a cool salty breeze blowing in off the water and the blue-green hills of the city up ahead. It was almost five, and the outbound lanes were mobbed, sweaty tangles of bumper-to-bumper frustration. But there was barely another car on my side of the road. I suddenly thought of Boston, and I laughed. It would be raining there, still, and the streets would be filled with the long, dour faces of people trying to convince themselves that spring really was on its way—or at least would be once exams were over.

Boston seemed so far away, and so ridiculous. Just then

I rounded a corner and the whole side of a hill bade me WELCOME TO SAN FRANCISCO.

I realized that I shouldn’t let myself get too carried away, that I should stay cool for the work ahead. But I felt so good about being back in California that I just couldn’t feel anything else. I couldn’t get uptight about meeting Musty, and I couldn’t feel all the small, sobering, paranoiac things that I should’ve been feeling, that I was supposed to be feeling. Just before I’d left Boston, John had given me the rundown on Musty, so that I could get good and paranoid about doing business with him. Being paranoid was supposed to make me cautious, discreet, cool about the whole riff. But what John told me just made me more confident than ever.

Because Musty was big. At twenty-three he was one of the biggest and most successful dealers in the country.

Which meant that his scene was a lot different from most other dealers’. Most of them, when they’re doing lots of ten or fifteen or twenty bricks at a time, think they’re moving a lot of dope. They figure they’ve got a good hustle going, and for the most part, they do. But they’ve got one hang-up, and that is their dependence on a supplier. In that respect they’re as helpless as the little guy who picks up a street lid now and then on his way home from work. And they can get burned and ripped off and hustled in a thousand different ways, just like that little guy.

Because they’re not in control of what’s going down. They’re just taking part.

Musty was in control. He did only one kind of job, and he did it extraordinarily well. Musty ran lots of two thousand kilos—no more, no less on any given run—across the border from Mexico. He dumped them in San Diego, in his own warehouses, and there they sat until they were shipped out in broken-down lots to New York. Musty kept his hand in the operation up to the point when the bricks were shipped, his own art-supplies front doing the job. But after that he was through with it; he took his cut and split. That way anything that was busted, either in New York, or on the way back to California, was almost impossible to pin on him. For all the narcs ever knew, the stuff was coming in through the New York Port Authority, right under their noses.

Musty ran a tight operation, with everyone from the Federales to the Customs people to the Mexicans who drove the trucks and airplanes being liberally paid off. He wasn’t just careful, though; he had class. When it came time for a shipment, he went down to the Mexican plantations himself. He was friends with the plantation owners he bought from and he spoke fluent Spanish. His concern did not go unnoticed by the sellers, and as a result his marijuana was only the purest, his bricks the heaviest. They were almost always at least thirty-two ounces—dry—with very few sticks and no stones or clay. On a market that’s usually full of oregano and gasoline-cured or otherwise hopelessly souped-up garbage, his dope was highly regarded. And it always brought a good price.

The most impressive thing about his operation was that he’d been running it for almost four years without a hint of trouble or a cramp in his style. A record like that demands respect, whether you’re behind the law or trying to keep ahead of it. The IRS people in San Diego had finally gotten on his back a few months before, but it’d been nothing serious, just a lot of irritating questions, and he’d simply stepped out of town for a while. To San Francisco, which was now his company headquarters.

3

JOHN HAD MET MUSTY EARLIER in the spring, on the Massachusetts Turnpike. John was test-driving the Ferrari he’d gotten the week before, seeing how it performed on the road. And Musty was bumming around the East, California style, with a pack on his back and his thumb out dangling. So John had picked him up and they were rolling along at maybe eighty, nobody saying anything and Musty no doubt sitting there thinking, What a bummer this is, to ride in this car with a straight creep—thinking this because in California anybody who smokes dope looks like he smokes dope, and Musty wasn’t used to the Eastern style yet. So when John, with his maroon Ferrari and his J. Press suit and his Newport accent, opened the glove compartment to reveal a pound bag of clean Michoácan, Musty blew his mind. The dope had come from one of Musty’s kilos that was nothing but buds and flowers to begin with; he just started laughing, while he rolled a few joints. John rolled up the windows so the smoke wouldn’t get out, and they both managed to get high as the sky before they hit the Newton tolls.

Which is a sad pun, for hit the Newton toll booth they did, going about twenty-five. Drove right up the cement fender and piled into the little box the toll guy stands in. Seemed that John, who was never a good driver, had a little trouble maneuvering his machine after a few joints. The toll guy was terrified, expecting to find some epileptic old lady who’d had a coronary. Instead, he was greeted by two very stoned young men, laughing hysterically and wiping the tears from their eyes. Completely unscathed, both of them, but not looking particularly grateful for it.

When the cop came, he told John that he was a very lucky guy. The cop also said some other things about Rich Motherfuckers and Kids Today. Everybody is interested in Kids Today, even the cops. He asked John how he happened to total his brand new Ferrari and John explained about the faulty disc brakes—these crummy little Italian imports, you know, they’re all the same—and the cop farted.

Then he drove John and Musty back to a gas station where they could call for someone to pick them up. John sat in the front seat, because he had a suit on and looked respectable. Musty sat in the back. The cop talked to John first, giving him some more about Rich Motherfuckers and Damage to Public Property and asking how his old man liked picking up the tab. Then the cop looked in the rear-view mirror and asked Musty how long it had been since he had taken a bath and whether he thought he was Jesus Christ, with hair like that. The cop also said he had fought in the war, he wanted them both to know, in the goddamn war.

To change the subject, John suggested that it must be tough work to be a state trooper. The cop mellowed at this and admitted that it was tough work. Everybody thought it was a great job to be a state trooper, he said. Everybody thought it was all glory and gravy. Everybody wanted to be a trooper, but they didn’t have no fucking idea, it was hard work and no joke.

John got off with a State Warning. Musty was told to be out of the state within forty-eight hours.

That was the way John worked. He needed to be with a person only about fifteen minutes before he knew what his weak spot was, and how to go to work on him. It didn’t matter if that person was a cop, or a professor, or a freak. Fifteen minutes. Anyway, John’d put his finger on Musty’s weak spot as efficiently as he’d managed the trooper. And before Musty said goodbye to Massachusetts, he’d agreed to sell dope to John in small lots, so long as the pickup was made on the West Coast. Musty, who never did anything less than two thousand kilos, and never touched his dope after it was in San Diego.

So I was on my way to meet Musty.

4

TRAFFIC WAS HEAVIER GOING OVER the Bay Bridge, but I made the corner of Ashby and Telegraph by five-thirty. From there it was just a few blocks to Musty’s address, 339 Holly Street, in the middle of a quiet neighborhood of clean, pink-and-white stuccos with palm trees and clipped lawns. There was nobody on the street to stare at the straight honky who jumped out of a green Mustang with a suitcase in his hand and went up to ring 339.

The suitcase was a little thing John had rigged up, small enough to fit under an airplane seat, and lined with aluminum to keep the dope smell in. It also had internal and external locks to disappoint inquisitive cops. A sealed package of any sort requires a specific search warrant before it can be legally opened. Altogether a neat and reassuring way to travel.

I rang the buzzer beneath the name on the mailbox: Padraic O’Shaugnessy. No wonder they called him Musty. Then I waited, and when nothing happened I pushed the buzzer again. The apartment was on the second floor, and I could faintly hear it ringing up there. But nothing else, no footsteps or talking or other noise.

I began to get irritated, because I was right on time and they should have been there to open the door

for me when I came up the steps. I couldn’t figure out where they could be, but then I didn’t really give a damn. I just didn’t dig standing around like the Fuller Brush man, waiting for somebody to come to the door.

Finally I went back to the car and started reading the Tribe I’d picked up on Telegraph. What a drag it was, this waiting. I pulled out my own little traveling stash, rolled a joint, and blew it, trying to relax.

I’d been sitting there half an hour when I decided to get something to eat. I could never eat on planes, and after the six-hour flight I was hungry as hell. The stoned hungries, I might add, which is what the Now Generation is all about. A normal case of the hungries anyone with a will can sit out, but the stoned hungries are merciless. When dope eventually gets legalized, it’ll be the A & P lobby that’s responsible. How can you argue against a drug that keeps you eating regularly, sleeping regularly, and buying a six-pack of Pepsi every day? No way, in America.

I’d just started the car when I heard sirens. I was wondering how close the fire was, when the patrol cars came screeching around the corner, going the wrong way on a one-way street, and pulled up in front of 339. Behind the patrol cars were two Ford sedans, loaded with narcs. They had a cop driving, so it looked like they weren’t just dropping in to pass the time of day. I sank down in my seat, and waited.

The bust moved very quickly, and very efficiently. The cops jumped out of the patrol cars and staked the house out, three in the rear and three up front. Two others headed for the front door; one had an ax and one had a portable vacuum cleaner.

The narcs spread out behind the cops, five of them going into the house. They were fingering their lapels and hitching up their pants nervously, like they expected some trouble. Which was absurd, because anyone as big as Musty wouldn’t hassle cops. But it appeared from my bucket-seat foxhole as though they might be planning to shoot first and ask questions later. Oakland heat, it will be remembered, have that habit.