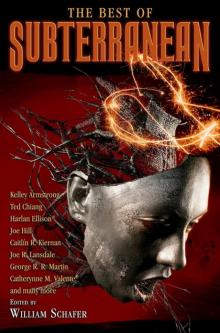

The Best of Subterranean, Page 1

William Schafer

The Best of Subterranean

Edited by William Schafer

Subterranean Press

2017

Subterranean Press 2017

The Best of Subterranean

Copyright © 2017 by William Schafer. All rights reserved.

Dust jacket illustration Copyright © 2017 by Dave McKean. All rights reserved

Interior design Copyright © 2017 by Desert Isle Design, LLC. All rights reserved.

First Edition

ISBN 978-1-59606-837-7

Subterranean Press

PO Box 190106

Burton, MI 48519

subterraneanpress.com

Table of Contents

Title Page

Perfidia by Lewis Shiner

Game by Maria Dahvana Headley

The Last Log of the Lachrimosa by Alastair Reynolds

The Seventeenth Kind by Michael Marshall Smith

Dispersed by the Sun, Melting in the Wind by Rachel Swirsky

The Pile by Michael Bishop

The Bohemian Astrobleme by Kage Baker

Tanglefoot by Cherie Priest

Hide and Horns by Joe R. Lansdale

Balfour and Meriwether in the Vampire of Kabul by Daniel Abraham

Last Breath by Joe Hill

Younger Women by Karen Joy Fowler

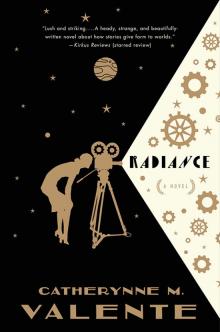

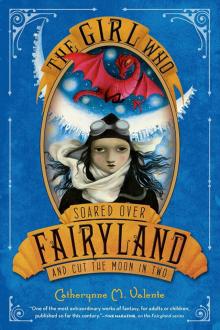

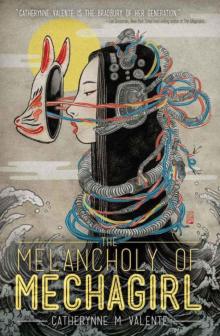

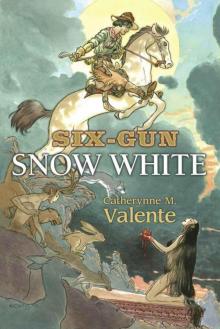

White Lines on a Green Field by Catherynne M. Valente

The Least of the Deathly Arts by Kat Howard

Water Can’t be Nervous by Jonathan Carroll

Valley of the Girls by Kelly Link

Sic Him, Hellhound! Kill! Kill! by Hal Duncan

Troublesolving by Tim Pratt

The Indelible Dark by William Browning Spencer

The Prayer of Ninety Cats by Caitlín R. Kiernan

The Crane Method by Ian R. MacLeod

The Tomb of the Pontifex Dvorn by Robert Silverberg

The Toys of Caliban by George R. R. Martin

The Secret History of the Lost Colony by John Scalzi

The Screams of Dragons by Kelley Armstrong

The Dry Spell by James P. Blaylock

He Who Grew Up Reading Sherlock Holmes by Harlan Ellison®

A Small Price to Pay for Birdsong by K. J. Parker

The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling by Ted Chiang

A Long Walk Home by Jay Lake

For Gretchen, with all my love

Perfidia

by Lewis Shiner

“That’s Glenn Miller,” my father said. “But it can’t be.”

He had the back of the hospital bed cranked upright, the lower lid of his left eye creeping up in a warning signal I’d learned to recognize as a child. My older sister Ann had settled deep in the recliner, and she glared at me too, blaming me for winding him up. The jam box sat on the rolling tray table and my father was working the remote as he talked, backing up my newly burned CD and letting it spin forward to play a few seconds of low fidelity trombone solo.

“You know the tune, of course,” he said.

“ ‘King Porter Stomp.’ ” Those childhood years of listening to him play Glenn Miller on the console phonograph were finally paying off. “He muffed the notes the same way on the Victor version.”

“So why can’t it be Miller?” I asked.

“He wouldn’t have played with a rabble like that.” The backup musicians teetered on the edge of chaos, playing with an abandon somewhere between Dixieland and bebop. “They sound drunk.”

My father had a major emotional investment in Miller. He and my mother had danced to the Miller band at Glen Island Casino on Long Island Sound in the summer of 1942, when they were both sixteen. That signature sound of clarinet and four saxes was forever tied up for him with first love and the early, idealistic months of the war.

But there was a better reason why it couldn’t have been Miller playing that solo. If the date on the original recording was correct, he was supposed to have died three days earlier.

* * *

The date was in India ink on a piece of surgical tape, stuck to the top of a spool of recording wire. The handwritten numerals had the hooks and day-first order of Europe: 18/12/44. I’d won it on eBay the week before as part of a lot that included a wire recorder and a stack of 78s by French pop stars like Charles Trenent and Edith Piaf.

It had taken me two full days to transfer the contents of the spool to my computer, and I’d brought the results to my father to confirm what I didn’t quite dare to hope—that I’d made a Big Score, the kind of find that becomes legend in the world of collectors, like the first edition Huck Finn at the yard sale, the Rembrandt under the 19th century landscape.

On my Web site I’ve got everything from an Apollo player piano to a 1930s Philco radio to an original Wurlitzer Model 1015 jukebox, all meticulously restored. During the Internet boom I was shipping my top dollar items to instant Silicon Valley millionaires as fast as I could find them and clean them up, with three full-time employees doing the refurbishing in a rented warehouse. For the last year I’d been back in my own garage, spending more time behind a browser than trolling the flea markets and thrift stores where the long shots lived, and I wanted to be back on top. It wasn’t just the freedom and the financial security, it was the thrill of the chase and the sense of doing something important, rescuing valuable pieces of history.

Or, in this case, rewriting history.

* * *

On the CD, the song broke down. After some shifting of chairs and unintelligible bickering in what sounded like French, the band stumbled into a ragged version of “Perfidia,” the great ballad of faithless love. It had been my mother’s favorite song.

My father’s eyes showed confusion and the beginnings of anger. “Where did you get this?”

“At an auction. What’s wrong?”

“Everything.” The stroke had left him with a slurping quality to his speech, and his right hand lay at what should have been an uncomfortable angle on the bedclothes. The world hadn’t been making much sense for him for the last eight months, starting with the sudden onset of diabetes at age 76. With increasing helplessness and alarm, he’d watched his body forsake him at every turn: a broken hip, phlebitis, periodontal disease, and now the stroke, as if the warranty had run out and everything was breaking down at once. Things he’d done for himself for the five years since my mother’s death suddenly seemed beyond him—washing dishes, changing the bed, even buying groceries. He could spend hours walking the aisles, reading the ingredients on a can of hominy, comparing the fractions of a pound that separated one package of ground meat from another, overwhelmed by details that had once meant something.

“Who are these people? Why are they playing this way?”

“I don’t know,” I told him. “But I intend to find out. Listen.”

On the CD there was a shout from the audience and then something that could have been a crack from the snare drum or a gunshot. The band trailed off, and that was where it ended, with more shouts, the sound of furniture crashing and glass breaking, and then silence.

“Turn it off,” my father said, though it was already over. I took the CD out and moved the boom box back to windowsill. “It’s some kind of fake,” he finally said, more to himself than me. “They could take his solo off another recording and put a new background to it.”

“It came off a wire recorder. I didn’t pay enough for it to justify that kind of trouble. Look, I’m going to track this down.”

“You do that. I want to know what kind of psycho would concoct something like this.” He waved his left hand vaguely. “I’m tired. You two go home.” It was nine at night; I could see the lights of downtown Durham through the window. I’d been so focused on the recording that I’d lost all

sense of time.

Ann bent down to kiss him and said, “I’ll be right outside if you need me.”

“I’ll be fine. Go get something to eat. Or go to the motel and sleep, for God’s sake.” My father had come to North Carolina for the VA hospital at Duke, and Ann had flown in from Connecticut to be with him. I’d offered her my guest room, 25 miles away in Raleigh, but she’d insisted on being walking distance from the hospital.

In the hallway, her rage boiled over. “What was the point of that?” she hissed.

“That’s the most involved I’ve seen him since the stroke. I think it was good for him.”

“Well, I don’t. And you could at least have consulted me first.” Ann’s height and big bones had opened her to ridicule in grade school, and for as long as I could remember she’d been contained, slightly hunched, given to whispers instead of shouts.

“Do you really need to control my conversations with him now?”

“Apparently. And don’t make this about me. This is about him getting better.”

“I want that too.”

“But I’m the one who’s here with him, day in and day out.”

It was easy to see where this was headed, back to our mother again. “I’ve got to go,” I said. She accepted my hug stiffly. “You should take his advice and get some rest.”

“I’ll think about it,” she said, but as the elevator doors closed, I could see her in the lounge two doors down from his room, staring at the floor in front of her.

* * *

I had email from the seller waiting at home. Her initial response when I’d written her about the recorder had been wary. I’d labored hard over the next message, offering her ten percent of anything I made off the deal, up to a thousand dollars, at the same time lowballing the odds of actually selling it, and all the while working on her guilt—with no provenance, the items were virtually worthless to me.

She’d gone for it, admitting picking everything up together at one stall in the Marché Vernaison, part of the vast warren of flea markets at SaintOuen, on the northern edge of Paris. She wasn’t sure which one, but she remembered an older man with long, graying hair, a worn carpet on a dirt floor, a lot of Mickey Mouse clocks.

I knew the Vernaison because one of my competitors operated a highend stall there, a woman who called herself Madame B. The description of the old man’s place didn’t ring any bells for me, but the mere mention of that district of Paris made my palms sweat.

My business gave me an excuse to read up on music history. I already knew a fair amount about Miller’s death, and I’d gone back to my bookshelves the night before. Miller allegedly took off from the Twinwood Farm airfield, north of London, on Friday, December 15, 1944. He was supposed to be en route to Paris to arrange a series of concerts by his Army Air Force Band, but the plane never arrived. Of the half dozen or more legends that dispute the official account, the most persistent has him flying over on the day before, and being fatally injured on the 18th in a brawl in the red light district of Pigalle. Pigalle was a short taxi ride from the Hotel des Olympiades, where the band had been scheduled to stay, and the Hotel des Olympiades was itself only a short walk from the Marché Vernaison.

I walked out to the garage and looked at the wire recorder where it sat on a bench, its case removed, its lovely oversized vacuum tubes visible from the side. I’d recognized it in the eBay photos as an Armour Model 50, manufactured by GE for the US Army and Navy, though I’d never seen one firsthand before. The face was smaller than an LP cover, tilted away to almost meet the line of the back. Two reels mounted toward the top each measured about four inches in diameter and an inch thick, wound with steel wire the thickness of a human hair. More than anything else it reminded me of the Bell & Howell 8mm movie projector that my father had tortured us with as children, showing captive audiences of dinner guests his home movies featuring Ann and me as children and my mother in the radiant beauty of her 30s.

The wire recorder hadn’t been working when it arrived, but I’d been lucky. Blowing a half century’s worth of dust off the electronics with an air gun, I’d found the broken bit of wire that had fallen into the works and caused a short. That and replacing a burnt-out power tube from my extensive stock of spare parts was all it had taken—apart from cleaning the wire itself.

The trick was to remove the corrosion without affecting the magnetic properties of the metal. I’d spent eight hours running the wire through a folded nylon scrub pad soaked in WD40, letting the machine’s bailers wind the wire evenly back on the reel, stopping now and then to confirm there was still something there. Then I’d jury-rigged a bypass from the built-in speaker, through a preamp and into an eighth-inch jack that I could plug into my laptop. With excruciating care, I’d played it into a .wav file and worked on the results with CoolEdit Pro for another hour, trying to control the trembling in my hands as I began to realize what I had.

* * *

When I got to the hospital in the morning, my father was reading the newspaper. Ann was still in the same clothes I’d last seen her in; she’d already had circles under her eyes, so it was hard to say if they were deeper. “You’re here early,” she said, with a smile that failed to cover the implied criticism.

“I’m on a plane to Paris tonight.”

“Oh really?”

“You going to find out about that tape?” my father asked. “That’s the idea. My travel agent found me a cheap cancellation.”

“How lucky for you,” Ann said.

“This is business, Ann.” I stifled my reflex irritation. “That recording could be worth a fortune.”

“Of course it could,” she said.

“Don’t give those French any more of your money than you have to,” my father said.

“Oh, Pop,” I said. “Don’t start.”

“We had to bail their sorry country out in World War II, and now—”

“No politics,” Ann said. “I absolutely forbid it.”

I sat on the edge of the bed next to him. “You’re not going to die on me, are you, Pop? At least not until I get back?”

“What makes you so special that I should wait for you?”

“Because you want to see how this turns out.”

“I already know it’s a fake. But there is the pleasure of saying I told you so. You’d think I’d get tired of it after all these years, but it’s like fine wine.”

I leaned over to hug him and his left arm went around my back with surprising power. He had two days’ growth of beard and the starchy smell of hospital soap. “I’m serious,” I said. “I want you to take care of yourself.”

“Yeah, yeah. If you bag one of those French girls, ask if her mom remembers me.”

“I thought you were only in Germany.” His unit had liberated Dachau, but he never talked about it, or any other part of the war.

“I got around,” he shrugged. His left arm relaxed and I pulled away. “Don’t take any wooden Euros.”

Ann followed me out, just as I knew she would. “He’ll be dead by the time you get back. Just like—”

“I know, I know. Just like Mom. It’s less than a week. The doctors say he’s out of danger.”

“No, he’s not.” She was crying.

“Sleep, Ann. You really need to get some sleep.”

* * *

I myself slept fitfully on the way over, too cramped to relax, too tired to read, but my spirits lifted as soon as I was on the RER from DeGaulle to the city. There was no mistaking the drizzly gray October world outside the train for the US, despite billboards featuring Speedy Gonzales, Marilyn, Disneyland, Dawson’s Creek. The tiny hybrid cars, the flowerboxes in the windows, even the boxy, Bauhaus-gone-wrong blocks of flats insisted that excess was not the only way to live. It was a lesson that my country was not interested in learning.

I’d been able to get a room at my usual hotel, a small family place in the XVIIth Arrondisement, a short walk from the Metro hub at Place de Clichy and a slightly longer one from Montmartre an

d Pigalle. I stopped at the market across the street to pick up some fresh fruit and exchanged pleasantries with the clerk, who remembered me from my previous trip. The hotelier remembered me as well, and found me a room that opened onto the airshaft rather than the noise of the street.

The bed nearly filled the tiny room, and it called to me as soon as the door closed. If I stayed awake until 10 or 11 PM I knew my biological clock would reset itself, so I forced myself to unpack, drink a little juice, and wash my face.

“Hey, ho,” I said to the mirror. “Let’s go.”

The number 4 Metro line ended at Porte de Clingancourt, the closest stop to the markets. I walked up into a gentle rain and a crowd of foot traffic, mostly male, mostly black and/or Middle Eastern, dressed in jeans, sneakers, and leather jackets, all carrying cell phones, talking fast and walking hard.

I headed north on the Avenue de la Porte de Clingancourt and the vendors started within a couple of blocks. These were temporary stalls, made of canvas and aluminum pipe, selling mostly new merchandise: Indian shawls, African masks, tools, jeans, batteries, shoes. Still, it was like distant music, an invocation of the possibilities ahead.

I passed under the Boulevard Peripherique, the highway that circles the entire city, and the small village of flea markets opened up on my left, surrounded by gridlocked cars and knots of pedestrians. The stalls here were permanent, brick or cinderblock single-story buildings with roll-down metal garage doors instead of front walls, and they were crammed with battered furniture, clothes, books, and jewelry. Deeper inside, in the high-end markets like the Dauphine and the Serpette, the stalls would have glass doors, oriental rugs, antique desks, and chandeliers.

I walked north another block, then turned left into the Rue de Rossiers, the main street of the district. A discreet metal archway halfway down the block marked the entrance to the Marché Vernaison in white Deco letters against a blue background. Twisting lanes, open to the rain, wove through a couple of hundred stalls, some elaborate showplaces, like my friend Madame B’s, some dusty, oversized closets piled with junk. As in any collector’s market, the dealers were each other’s best customers; I watched a man in a wide polyester tie and a bad toupee hurry past with a short wooden column in each hand and a look of poorly concealed triumph on his face.